Mary Stevens09 Jan 2026

2025 was a huge year for Friends of the Earth’s AI advocacy work and internal strategy. Holding the line between responsible adoption alongside critical advocacy hasn’t always been straightforward, but in both domains, the Experiments Team has been playing a crucial role in shaping the conversation.

What did the landscape look like in 2025?

We spotted 5 trends.

1. AI in the UK entered a new phase. Following the publication of the government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan in early 2025, and follow-up announcements (for example around Growth Zones), AI and its associated infrastructure have suddenly become a lot more ‘real’, both in physical presence and real-world impacts. Adoption within the not-for-profit sector has also been mainstreamed. But as Ajaya Haikerwal showed in relation to the climate movement in Australia, uncertainty and ethical concerns mean that formal organisational policies often lag behind, and more risky unsanctioned ‘shadow usage’ is high. Projects like Tech 4 Good South West’s AI Living Lab have been helping bridge this gap for impact-led organisations.

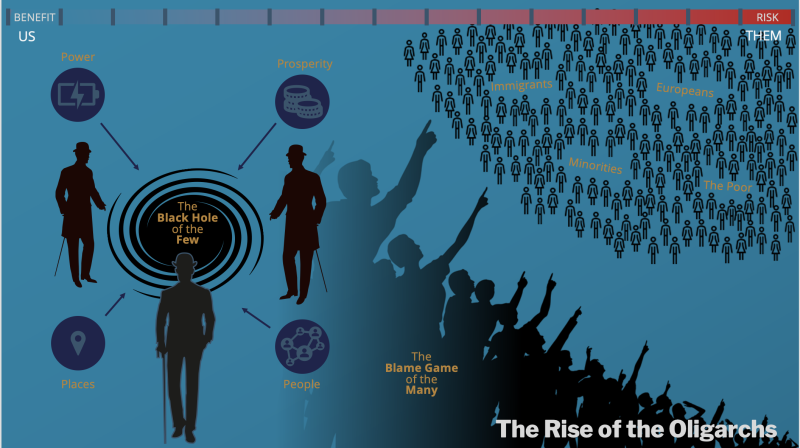

2. AI as an engine of inequality. There’s a growing awareness of the way in which the current business models of AI technologies are accelerating inequality on an incomprehensible scale. This opinion piece from the Big Issue sums it up nicely. It’s no surprise that this is the context in which conversations about wealth taxes on the super-rich have become mainstream.

3. New global solidarities are emerging. Thanks to my involvement with more international coalitions, I have heard directly from campaigners in Brazil, Congo and Taiwan, all experiencing the direct and harmful impacts from different parts of the AI supply chain. I am not alone in noticing strengthening global connections. AI was integrated as a conference theme at the climate COP for the first time, which both created a platform for lobbying and greenwashing, as well as an opportunity for dissenting voices at the People’s Summit. It’s been exciting to see Amnesty UK’s anti-racism network start to pick up this angle, and we know their work has resonated with the young people in our Environmental Justice Collective.

4. A wider lens on digital sustainability. Interest in the environmental impact of data centres has also prompted a renewed conversation about our collective digital ‘shadow’. AI growth is driving data centre expansion, but at present data centres are estimated to contain 65% ‘dark’ data (data that is used once or not at all). What are the real costs of all our smart devices, for example? I really enjoyed exploring some of these issues with Arielle Tye in this podcast episode. Time to start getting ready for Digital Cleanup Day 2026?

5. The resistance movement is growing. Driven by spiking electricity prices and the lack of corporate accountability, a coalition of 230 environmental groups in the USA recently demanded a moratorium on new data centre construction. And organisations like Media Justice are building a powerful movement on the ground, with a focus on environmental racism. This bold organising in difficult circumstances will be inspirational to many.

What to look out for in 2026 – opportunities for advocacy

Legal challenges against hyperscale data centres

Early 2026 will see some key moments that will set the pattern for the year to come. A judgement on Foxglove and Global Action Plan’s landmark Planning Appeal is expected soon, and is likely to determine whether or not future large-scale infrastructure should be subject to Environmental Impact Assessment.

In general, as awareness of data centres grows and more AI Growth Zones are announced, we can expect more sites of conflict between local communities and developers. In particular, alongside our allies at Axe Drax and Biofuelwatch we will be keeping a close eye on Drax’s AI data centre bid, which, if successful, will extend an unwarranted lifeline to the UK’s single largest carbon emitter.

Conflict between local communities and developers

Communities could soon see their opportunity to influence developments further reduced as the government plans to consult on allowing applicants for larger data centres to opt into the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects regime (NSIPs) - taking responsibility for consenting out of the hands of local authorities and handing it over to central government. We know the Government has met with Tech industry lobbyists on this issue, but civil society groups have not been consulted. The consultation on the National Policy Statement (that will underpin the designation of data centres as Nationally Significant Infrastructure) will be a key opportunity to galvanise and coordinate groups keen to see a more democratic and open approach to AI expansion.

London demands stringent conditions on new data centre development

Greater London is where tensions between the needs of local people and the interests of tech investors are most acute. We’ve already seen warnings from the London Assembly that data centres are putting housing targets at risk, with plans for new hyper-scalers demanding as much energy as all the housing in whole boroughs. New recommendations from the Planning and Regeneration Committee suggest much more stringent conditions, including mandating data centres to contribute to heat networks and the need for whole life-cycle carbon assessments. Where London leads, others could be pushed to follow.

Shareholder and worker activism

Finally, there is potential for a rise in shareholder and worker activism. In 2024 Holly and Will Alpine turned the tables on Microsoft, setting up the Enabled Emissions campaign, to draw attention to the role of Big Tech in extending the fossil fuel age. Microsoft is often one of the largest holdings in ‘ethical’ pension portfolios, so if institutional investors start to feel the heat from their members, this could be an important lever for change. In 2025 employee and investor pressure also led to Microsoft terminating the Israeli military’s access to its technology, as well as undermining claims that data centres were essential to local economic growth (where were the local benefits to storing millions of Palestinian phone calls in the Netherlands?).

What’s needed in 2026

More joined-up thinking by government and campaigners

A shift in the UK’s collective relationship to AI technologies will require two closely related developments. The first – a high-level goal – is that there must be a much more joined-up strategic approach to AI growth and development, in contrast to the piecemeal venture capital-led model the Government has been pursuing to date. This applies first and foremost to infrastructure: how much compute is actually needed to meet our goals and stick to (or preferably even accelerate) climate, nature and social justice targets? Where should it be sited, how should it be powered, and how should the benefits be distributed? This is in sharp contrast to the current investment-led position, which prioritises the interests of (US-based) tech capital above all else.

But in order to push for this more coherent vision there must be much more joined-up campaigning and advocacy. Friends of the Earth is in the early stages of closer collaboration with other NGOs in this sector, but (beyond academia) funders have yet to step up to resource this existential work with anything like the urgency it requires. (Special thanks to Rachel Coldicott and the Careful Industries team for helping with the initial thinking earlier in the year).

More support to enable digital transformation

At the same time, civil society organisations must be helped to engage constructively in this context; charities just as much as small businesses need a package of support to enable responsible digital transformation. This twin-position can feel awkward, but as others have put it, it’s a bit like driving a car to get around whilst advocating for sustainable public transport.

Become more creative about how we talk about AI

Finally, campaigners and advocates need to get much more creative in how we talk about and envision AI-entangled futures. In Could Should Might Don’t: How We Think About the Future, futurist Nick Foster draws our attention to four common modes of futurist thinking, and highlights their pitfalls.

Thinking about AI is dominated by three of these modes:

- ‘could’, the sci-fi universe of benevolent robots overseeing a world of flying cars and towering glass cities (untethered from the restraints of a finite planet),

- ‘don’t’, the crippling dystopia of unstoppable AI partnered with tyrannical baddies, and

- ‘should’, driven by the seeming inevitability of data curves (projected lines of data centre growth, or energy use).

‘Might’ is the world of scenario-planning. This is theoretically open to a wider range of possibilities but is hamstrung by the paucity of our imagination about human-technology futures. If we want to escape these destinies, then there is a vital task for artists and creatives to help us all imagine alternatives, and, as Rob Hopkins puts it, to transform the poly-crisis into a poly-opportunity and cultivate our deepest longing for a different kind of future.

Two thoughts I am taking with me into the year ahead

As 2025 draws to a close there are two thoughts that I hope will act as a compass for AI advocacy in 2026. The first comes from Tim Kindberg, writer, creative technologist and ‘personal to planetary’ fellow at Bristol University. In a recent presentation he highlighted a key paradox: that whilst we are paying ‘accelerationist attention’ to AI when it comes to nature our posture is one of ‘slow neglect’. When all the signals and feedback we are receiving from the earth makes it abundantly clear that we need the reverse. What would it take to consciously shift this balance of attention? And the second I owe to Mother Cyborg, Detroit-based artist, technologist, activist, pioneer and recently artist in residence at Bristol University ESRC Centre for Sociodigital Futures. Her creative practice derives from a growing awareness that she wanted a tangible practice, beyond the zeros and ones of the online world. The power of Big Tech may seem unassailable but as she puts in this beautiful work:

I am freer for believing in change.

If you would like to discuss any of these ideas, please do get in touch and feel free to share them.