Mary Stevens16 Jul 2025

The challenges of delivering responsible AI

Disruptive technologies, such as AI, are not neutral in their impact. Who owns and steers the technologies and their future development matters and there are considerable ethical challenges in delivering responsible AI. Examples of AI impacts are wide ranging – from mineral and water extraction and energy usage to governance, bias and incentive alignment.

Friends of the Earth is concerned about such challenges and I was delighted to speak at a roundtable hosted by the Centre for Future Generations on ‘The missing link: addressing tech governance in the climate transition’ during London Climate Action Week. Participants at the event, held in a big City corporate law office, were a stimulating mix of venture capitalists, campaigners, management consultants and sustainability leads from big companies. And there was strong representation of folks from the USA, attracted to the freedom that London still presents to discuss topics that are becoming more and more dangerous in the US.

AI and a just transition

As Namita Kambli who hosted the rountable acknowledges, technologies like AI have a growing role in our climate transition. But sustainability and fairness can slip behind when speed and scale of innovation take priority over communities and the environment. And while transparency is an important first step, we must think about how to use it to tackle the power imbalances that are allowing capital and the tech sector to operate outside of the norms of democratic conversation.

Despite a temptation to lapse into technocratic language about frameworks and coordination at the roundtable, governance is fundamentally a set of questions about power, ownership and control. Who gets to make decisions about where our technology is heading? and who is accountable for them? I was pleased to hear the organisers set this out very directly at the start.

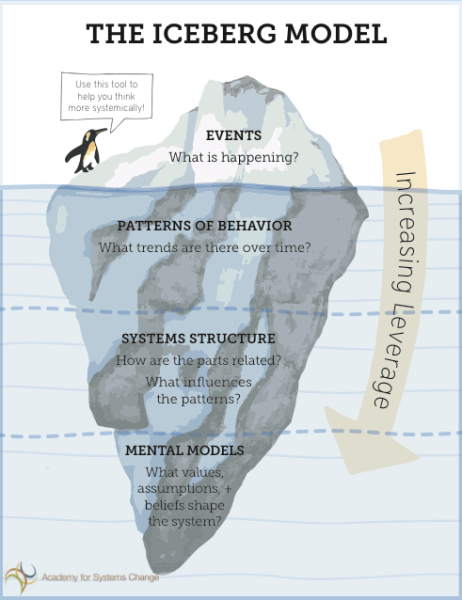

I was asked specifically to reflect on the emerging policy opportunities: what’s in our current toolbox to start bringing tech within planetary boundaries? I drew on Donella Meadows’s iceberg model and discussed how we might apply this to the current policy context around big tech - and specifically AI regulation.

Using the iceberg model

Events: what is happening?

In the UK context, there are a number of events to keep our eye on, such as the upcoming announcements around AI Growth Zones, and whether data centres will be designated as Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects under planning rules.

A long-term compute strategy is also due to be published this year, which will set out a roadmap for AI infrastructure investment. At the same time, we should pay attention to an alternative train of events in the EU, where legislation and standards that impose much tougher standards (for example through the revised Energy Efficiency Directive) are being rolled out.

Such events are important as they will determine the extent to which ordinary citizens have the power to influence infrastructure developments in their communities, even when they cause harm to people and nature.

Patterns: what trends are there over time?

In this category I would include a trend towards autocracy, or the exclusion of the ‘little people’ (all of us!) from decisions about this infrastructure on the basis of urgency/fear of missing out. There's also a pattern of exclusion of civil society actors, or indeed anyone who can speak on behalf of anything other than narrow economic interest, from the government’s decision-making structures.

A telling example is the government’s AI Energy Council, whose purpose is to balance the ‘clean energy superpower mission’ with the ‘commitment to advancing AI and compute infrastructure’ but includes only ‘industry heavyweights from the energy technology sectors’. Such language makes it abundantly clear that anyone else is considered a lightweight, whose views are not to be taken seriously. Even the Committee on Climate Change, the government’s independent advisors, is not part of the conversation.

Structures: how are the parts related? What influences the patterns?

Finance flows This is the space to consider the flows of finance and the regulatory landscape. What are the frameworks that force us to put people and planet in the service of profit, and not the other way round? The role of venture capital (VC) is important here. Growth in this sector is almost entirely driven by VC (rather than longer-term public sector investment, for example), with its rapacious appetite for huge investor returns. And VC is relentless in pushing the narrative that regulation is a barrier to innovation.

Institutional investors also have a role to play here; if you have an ‘ethical pension’ (i.e. divested from fossil fuels and weapons) you are almost certainly invested in big tech. How can we exercise more collective power in this space?

What about litigation? Last year the supreme court ruled that Surrey County Council’s decision to approve drilling for oil was unlawful because the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment didn't include an assessment of the downstream greenhouse gas emissions. Could this decision have a bearing on data centre development, and the lack of full lifecycle assessments for new developments? (Including, for example, the creation of e-waste, the fastest growing waste stream in Europe or their enormous demands for energy and water).

Mental models: what values, assumptions and beliefs shape the system?

These are the easiest to identify. But possibly the hardest to tackle. At heart is the assumption that growth is an end in itself, that the purpose of innovation and industrial policy is to promote this at any cost (don’t worry, technology will also mop up the damage later) and that infinite growth is possible and desirable on a finite planet. If digital technology is to be harnessed in service of thriving on a liveable planet, then we urgently need to address this question. What is this technology for? How much is enough? Who decides? What is a worthwhile use?

Other models

These questions can feel very daunting. But other models are out there (such as the Within Bounds declaration from the Green Screen Coalition), and allies in unlikely places. For example, in its recent report, the Royal Academy of Engineering, in partnership with the Chartered Institute of IT, and the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC) made a powerful case for the UK to become a world leader in ‘frugality and efficiency,’ in the context of just transition.

A systems approach requires us to act at multiple levels; we cannot take our eye off ‘events’, but it’s when the mental models start to shift that we will achieve the greatest impact. As a sector, our advocacy needs to be broad-based and joined up. There's lots of excellent work to point out the problems, but we must start working together on solutions, at every level from events to mental models. The time to influence the kind of AI development the planet needs is now.

If you would like to be part of this conversation and explore how we might influence the development of AI for good, we would love to hear from you.