Mary Stevens30 Nov 2021

A trip up to Glasgow for COP26 recently provided the ideal excuse to stop off in Lancaster and see for myself how Rachel Marshall and the Rurban Revolution team have been bringing the Hope Spots concept to life.

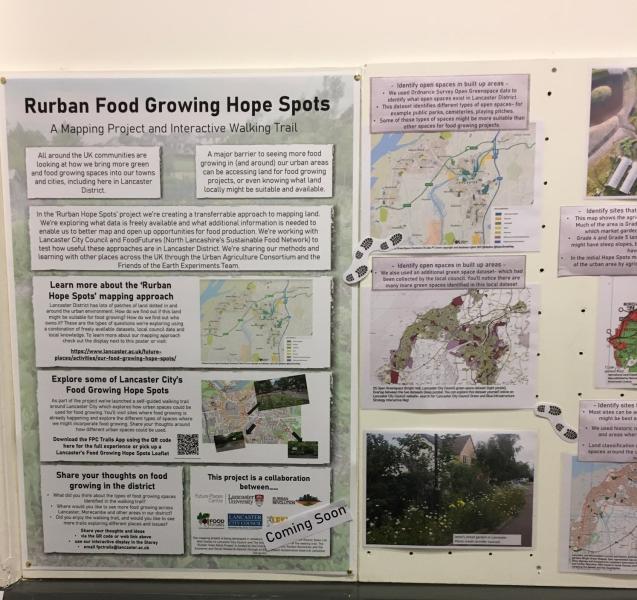

In 2019 we worked with Mark Thurstain and the Geofutures team to explore how we could overlay nature and social deprivation data to identify priority locations for tree planting and nature recovery in the Bristol and Bath greenbelt. We developed a prototype map and a shortlist of candidate locations. But the map was always just a means to an end – a way of prompting more action, or creative responses, to bring the Hope Spots to life.

Over the last six months it’s been exciting to see the project develop a new lease of life in Lancaster, where a team from the Future Places Centre at Lancaster University has taken up this challenge.

They have been working with Mark to adapt the model to look at food-growing locations, which in many ways feels like a better fit (tree planting locations are also now well served by our Woodland Opportunity Maps). The mapping work is still ongoing, but as part of the project they have developed a walking trail, linked to an app that helps people imagine alternative futures. So on Friday afternoon we set off up the hill from the station on a mini-journey of discovery.

The experience was not seamless. There are a few bugs and glitches in the app – all in the process of being fixed - but in many ways I like it the better for that. Innovation is bumpy and messy, a point it’s easy to forget when we are so used to a frictionless digital experience. There were three key learnings for me from the tour.

1. Start with inspiration.

It is hard to imagine how things can be different. We know that the climate crisis is beset by what Rob Hopkins (and others) describe as a ‘poverty of imagination’. Rachel had therefore wisely chosen to start the trail in a hidden but thriving community garden. Despite the season (few garden edibles really look their best in November) it was easier to see how the margins and edges of footpaths and existing green space could be transformed into something full of life and potential.

Scotch Quarry set a benchmark for all the subsequent locations: what would it take for them all to host spaces like this? Unfortunately for time reasons the tour was unable to take us to Claver Hill where permaculture design to manage flood water storage is challenging the assumptions that only cows can grow in flood plains, and that sites need to be closed off and private. Seeing flourishing projects planted seeds for the future in our minds.

2. Use the most appropriate technology.

Some walking trails use GPS technology; your location data triggers an audio clip (for example) to play as you approach the correct site. Drawing on previous experience installing trails in forests (where GPS can be unreliable), researcher Jan Hollinshead decided to use bluetooth beacons.

There are many advantages to this approach: it’s not cloud-based, so there’s no unnecessary data storage and a project’s energy footprint is reduced. Data cannot be stored so participants are not tracked and the hardware itself can easily be reprogrammed. The trail can be followed without requiring users to use their own data allowance. Beacons are also relatively easy to programme, so could be used as part of educational projects, supporting wider lessons about ownership of data. The relatively low-tech nature of this project reminded me of hardware-based community projects like this one in Detroit: not everything has to be managed through the big tech giants (even if in this case the app still did have to be hosted by Apple and Google).

3. Don’t expect answers – use the tech to ask better questions.

It would be easy to assume that if the inputs and code are sufficiently detailed then the Hope Spots’ methodology will automatically throw up the optimum locations for food growing. In fact, this is far from the case. The first iteration of mapping revealed candidate locations, but a workable list required Rachel’s in-depth knowledge of the geography and communities of Lancaster. There are a number of reasons for this: the publicly available data (e.g. Ordnance Survey green spaces data) is insufficiently detailed, so needed supplementing with data held by the Local Authority, and it then required someone who could spot the anomalies (the gaps, the inconsistencies) to ask for the right thing. Rather than providing answers, the data has opened up more questions: for example, what about historic sites, what do we know about where there used to be market gardens, or glasshouses, what range of sources do we need to access to find out more? On our walk through Lancaster several people stopped to say hello, (“Rachel knows everyone,” her colleagues explained).

‘Having a Rachel’ is key to turning ideas into action for a project like this; greening alleyways and corners relies far more on engaging the right people in the community than it does on data optimisation. But the tech does help Rachel decide where to focus.

We need to use tech to enhance our human capabilities – for personal connection, for multi-sensory observation - not to displace them. For the same reason, audio, not video is much more effective as a stimulus on a walking tour. Audio takes you more deeply into a place and can prompt you to look further, feel more. Video on the other hand takes you out of the place and into the screen.

At Lancaster University the challenge of how we use digital technologies to enhance our capabilities is shaping a lot of the thinking in the Future Places Centre. How can we use technology to make the invisible visible, like micro-plastic pollution for example - and use this to provoke further action? What role can Augmented Reality play here?

As we move into the darkest months and plants shed their leaves to nourish the soil, these are questions to sit with, and allow to sink in, to feed the next generation of slowly germinating ideas.