Mandy Holden18 Jan 2023

As several of our Local Nature Innovation Fund projects demonstrated, food - foraging, cooking, eating - has a high band width and individuals can work together as a group to create a range of activities that can be self-defined and work for different people. Darren from the Hull Food Partnership observed that growing veg and cooking seem to tap into the same parts of the brain as music, art, drama and are unifying across many and varied people.

Eating a range of fresh vegetables is increasingly important – whether for health or to reduce the impact of meat production on the planet and it’s good to start early with kids before their likes and dislikes get set in stone. Darren discovered that involving kids in the annual growing cycle of veg can encourage them to eat it and working with kids in schools is a great way to reach parents.

So how do you turn kids into advocates for growing veg and what are the obstacles?

"When we went out into the community, it just reconfirmed all the problems I know we have. Working parents don’t have the time and it’s almost insulting to go to them and say...Oh, come on! You can make the time to grow vegetables vertically...They look at you like you’re from Mars. That’s something we need to crack, and my solution is let’s get their children on board. They become advocates"says Amrish from V-Grow, who has been prototyping a vertical vegetable patch at St Philips Marsh Nursery School in Bristol this summer.

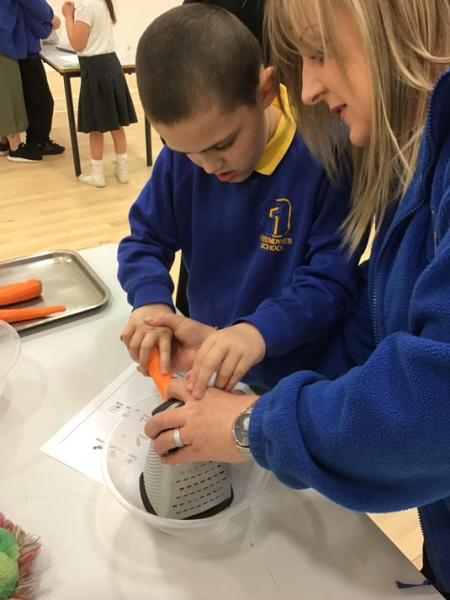

Children and young people can have a significant role in bringing the whole family along, Darren from Hull Food Partnership agrees. He devised a Summer Eating Challenge, inviting families from Tweendykes School, which supports students with special educational needs, to grow, cook and respond creatively to vegetables over the summer holidays.

But Darren calls for a curriculum that integrates nature and growing at its core

He discovered that the biggest obstacles to engaging kids in understanding food growing are the rigid demands of the curriculum and the disconnect between the school framework, timetabling and lack of understanding about horticultural practices.

Delivering the curriculum can leave little room for students to connect with nature and growing across the seasons. Tweendykes, which supports students with complex and often challenging needs, is unusual - Darren noted that they seem to have more room to manoeuvre than some mainstream schools. They are delivering the National Curriculum, but are responsive and flexible.

The importance of following a seasonal rhythm…

Darren passionately believes that growing veg and teaching about nature need to be in a structure that teachers are happy with and that follow a seasonal rhythm. Children need to be able to complete the learning experience – they should be able to move from sowing the seed to harvesting the fruit and understand that food growing is a system, not just a science. Only achieving part of that is actually a failure. The child harvesting food should be the first step in planning the timetable - otherwise you’re just teaching waste according to Darren.

"If a child takes a tomato and eats it or takes some courgettes and cooks with them, that almost needs to be the starting point. The timetable should start with the child’s experience, not with the needs of the curriculum" observes Darren.

Having worked with schools for many years, Darren says it often feels like they are on a moving conveyor belt and it’s really hard to take a breath and think about a different approach. The pressures don’t seem to be easing up. If anything, they seem to be getting worse.

…..and leadership in the school as well as the project

You also need an enthusiastic and committed teacher to champion the project and prioritise the children’s experience.

The project has brought some important fresh perspectives and ideas into the school to address an ongoing issue of the diets of young people, in this case with special needs. "I was blown away by the way Tweendykes carried the project. When they commit to something they commit to something completely. I might have set the spark, but they gave it energy."

In contrast, Darren has noticed that when students engage with growing in an ad hoc way there can be a vast disconnect. He describes watching primary school kids harvesting tomatoes. They don’t know much more than ‘harvest the red ones’ and haven't been engaged in the growing cycle. The caretaker tells them to take the veg or it will get thrown away. Darren didn’t see a single pupil eat a piece of fruit or veg from the garden the whole day.

"I don’t want to teach that harvesting food doesn’t matter. It teaches that there isn’t a point to it. If you don’t eat it, it’s just a bit of fun." If kids are growing broad beans, measuring them to see how much they’ve grown and then not eating them, they’re being taught that food growing is a science lesson, not a system. It’s interrupted learning.

Some early intervention points

Coming to schools with a well thought out offer is powerful. Darren explains his recipe for successful engagement:

- Bring a clear idea with strong objectives.

- Do the research, so teachers don’t have to. The more straightforward the end process, the more work has to go into the development. You can’t expect teachers to have time to go through recipes, eliminate 99% and choose the ones that all kids will be able to engage with.

- Offer a simple framework of lesson plans to follow.

- Provide resources. At the Tweendykes Veg Day, Darren made it easy by bringing along 15 graters, chopping boards and a big bag of carrots!

Make it visible and build on the interest it creates

Judit and Amrish from Flourishing in St Paul’s created a prototype for a vertical veg growing system at a local school which attracted interest from parents and passers-by and they used it as a basis for a workshop and teaching time to share their knowledge with the community.

Amrish explains how this stimulated his thinking – How can he make this relevant for children in schools? What might be different for primary, secondary or sixth form? He got the kit, costed out the system and is devising lesson plans to follow to get other schools building and using V-Grow systems, whilst linking the work to nutrition, the environment and mental wellbeing.

As a result of this experimentation, they have now been successful in securing additional funding to grow vegetables vertically in more schools.

Many of the Local Nature Innovation Fund projects concluded that having a tangible and visible prototype – be that a vertical growing system, seed library, booklet or urban garden - is important in engaging people. A school is a great place to visualise things, to engage kids and families across the community.

Integrate the whole school in the project

At Tweendykes, the Summer Eating Challenge was designed so all the students took part in initial activities delivered at school. No one was excluded from the activity because of capacity at home. Darren acknowledges that it’s too much to expect all families to take part in the home-based components, but 40% of students completed the entire challenge nonetheless.

Darren puts some of the success of the project down to the fact it involved the whole school. The new school year can feel like a deep change, so maintaining momentum can be a challenge. Because the programme was fully integrated, there was continuity across two academic years.

Returning to school in September, Darren has been round handing out certificates, seeds and aprons to take home. It’s important to keep families involved and leave behind a prompt for learning and remembering. Not forgetting gifts of appreciation for the teachers too.

Give schools ownership – even if it feels uncomfortable

Tweendykes contributed and adapted the ideas, even taking Darren’s recipe booklet and translating it into Makaton; a unique language programme that uses symbols, signs and speech to enable people to communicate.

Darren confesses that he was nervous that the objectives of the project would shift if he let go of control. With a strong enough framework in place, trusting others to take the work forward can generate great results.

These prototypes could be a glimpse of a possible future for the curriculum.

Darren is wondering about creating a ‘Handbook of School Horticulture’ next, explaining a timetable for growing that works with the school year timeline. Simple things, like getting growing early, so they can harvest before the summer holidays and knowing what to plant out in the autumn. Most gardeners understand it, but we need to put it into the hands of 5-year-olds and teachers.

This left us with some questions to ponder in our future work

What if...we grew a curriculum from harvest through to harvest?

What if...learning was centred around the continuity of a child’s experience?

What if...school life was integrated into the whole cycle of the growing season?

These are big dreams. Darren and Amrish have learned a lot about where to start.

If you'd like to find out more about these projects and what we learned from running the Local Nature Innovation Fund, get in touch.