Mary Stevens19 Nov 2025

What are the Transition Templates?

Understanding or mapping ‘the system’ is often the first step in planning any sort of experiment. To decide where we might have the most impact, we need to identify all the different actors, how they relate to each other and where power lies. It’s a principle that will be familiar to campaigners and designers alike (although they might call it different things). There’s no shortage of tools out there to do this.

However, when Bath Spa University invited us to partner on a project exploring the application of a new set of approaches to map the system and develop our approach to AI and digital sustainability, we saw an interesting opportunity. We felt taking part would both develop our systems practice and help us learn more about an area of practice and campaigning that was still relatively new territory for us.

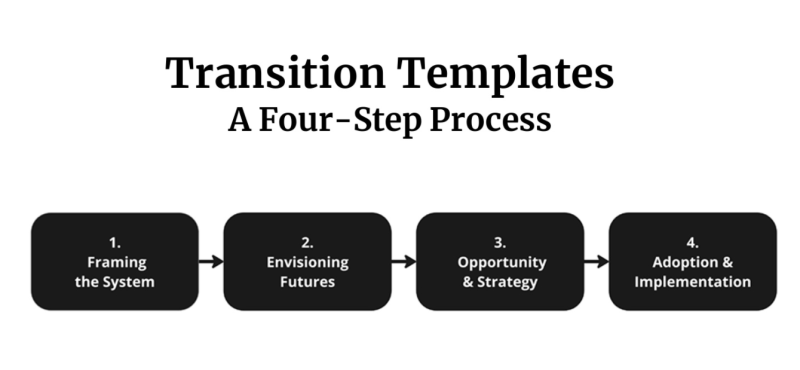

Dr Joanna Boehnert and her team at the Bath School of Design are testing a set of visual templates that aim to support organisations in developing practical and actionable plans for decarbonisation across five sectors of the UK economy. They call them ‘Transition Templates' and they work in four steps: from ‘framing the system’ to ‘adoption and implementation’.

In this article I describe how we’ve applied the templates to our work on Artificial Intelligence, what we have learned both about the practice and about the subject, and how we might use them in the future.

How do they support our work?

The templates have the potential to support our work in three ways.

- They bring together our futures work and systems practice (which can sometimes feel a bit abstract) with tools that feel familiar to our campaign planners.

- They provide a ready visual narrative or record of conversations (about stakeholders, for example).

- They can be used as a collaborative tool in a workshop setting - including to support the gaps in our understanding. We’ve not yet been able to do this for our AI work, but we can see the potential.

What have we learned from so far?

Framing the system

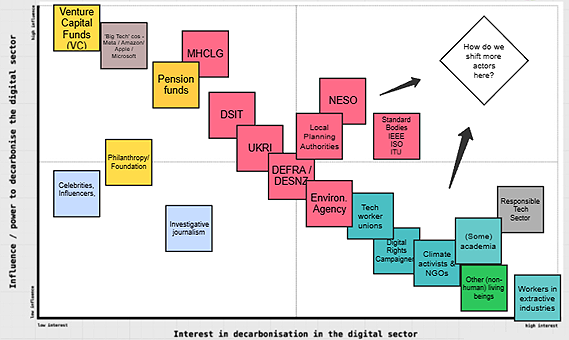

Building on a workshop hosted by Bath Spa, we started with an impact influence framework. This is a very familiar tool: most campaigns will have some version that they use for stakeholder mapping. Some familiar questions arose: how do we compare different types of influence, over a different timeframe? As an example, the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government can exercise very high influence over some types of specific decision, such as overturning a planning decision by a local authority - but how does this compare to the influence of the parts of government that could set rules for energy use?

What this exercise quickly revealed is that there are currently very few actors with both high interest and high influence in decarbonisation. Action planning (or tactics) should therefore focus on what's needed to shift key actors into the top right quadrant. How can we increase the influence of those who care deeply, but have little power, and engage those who don’t yet care about the ecological consequences of AI technologies but could do more (investors, for example)?

As an environmental justice organisation, we run all our ideas and campaign plans through a ‘Diversity and Justice analysis’. This analysis has a specific purpose, in making sure that our interventions don’t unintentionally make a given situation worse for disadvantaged groups, instead supporting them to achieve their goals.

The templates also include a similar step, encouraging participants to explore who benefits, who harms and who has agency in the digital decarbonisation. This is a crucial step, and can be effectively overlaid with an organisation's values. It can also serve to draw attention to which voices are, or are not present in the debate - an issue of which we were very conscious when developing the roundtable that informed our AI report with a focus on global majority voices.

Envisioning futures

Future visioning is often one of the hardest parts of campaign planning. It’s particularly tricky in this context where the whole conjuring trick of digital infrastructure is to render it invisible (so that we forget that the cloud is made of steel, and cables, and servers, and minerals and hard labour). How in this context can we imagine a regenerative future, when we struggle to even hold the reality of the present in mind?

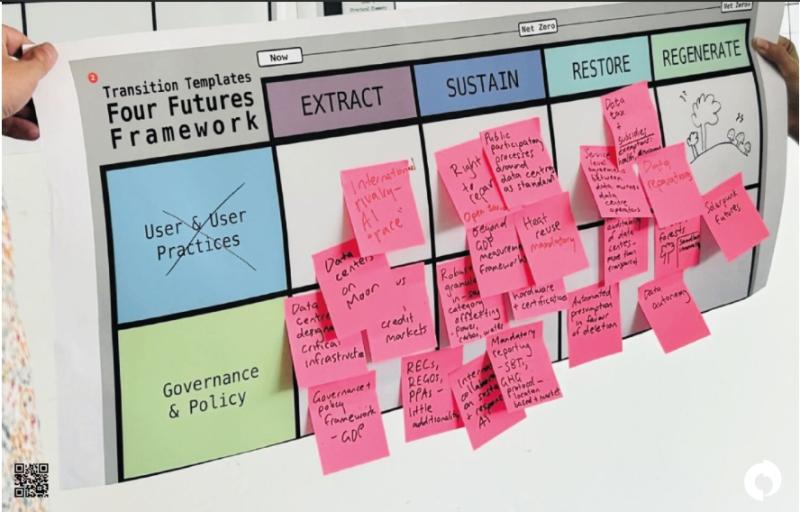

The Transition Templates seek to apply a four futures framework, adapted from the typology of sustainability approaches developed by Mang and Reed (and popularized outside of academia by Daniel Christian Wahl). This framework supports participants to map practices and interventions against the paradigm in which they sit (from ‘extract’ – the status quo – to ‘regenerate’). Our experience has often been that templates like this are valuable tools for synthesis, but they work less well for prompting and generating new visions. We would argue that the template needs to sit alongside, or follow on from, more creative and experiential approaches to bringing futures to life. These could encompass storytelling (and ironically, AI might have a role to play here), but far better would be a deeper, multi-sensory engagement with the living world and to let nature provide the clues that point towards new paradigms. As Fieke Jansen explains in a brilliant article that explores this dilemma:

"Can we imagine alternative infrastructural practices that restore and regenerate? Not to offer one quick fix but to challenge our understanding of what infrastructures are and whose interest they serve [..]. Only by shifting our worldviews away from capital accumulation, optimization, and growth towards good relations with the Land can we create alternative futures that prioritize people and planet over profit and capital."

A template, on its own, without the backing of a deeper enquiry, will always fall short here. But this, in itself, is a necessary realisation – and here the templates become part of an iterative, continuous design process, rather than an end in themselves.

Where next?

At Friends of the Earth, we’re currently thinking about how we map our own ecosystem of resistance and support in relation to data centre expansion, alongside other campaigning partners. As a coalition starts there’ll be a temptation to run fast and deploy tried and tested techniques. The value of this Transition Templates process will be in helping us in the necessary slowing down and stepping back - and specifically to highlight those areas for intervention that we may have overlooked, as well as the gaps in our understanding of the future.

Finally, the transition to a fossil-free future will never happen through the application of analytical tools alone, however well designed. We need to find ways of feeling possible futures in our bones and our souls. As Rob Hopkins explains, change-making needs to become the practice of cultivating our deepest longings for different ways of being in the world. Designers have a key role to play here. These tools have the potential to distil and collate some of that longing. But they cannot prompt it. For that, practitioners will need to continue to step out of the conference room, or the design studio, and into a relationship with each other, in the living world.