Mary Stevens13 May 2025

How might innovative design and action by communities make older and disabled people more able to cope with heatwaves – while making cities cooler, greener and fairer?

This is the challenge we put to a group of MSc students from the University of Bristol’s Centre for Innovation, alongside leading design and innovation consultancy Sparck, to explore not just how we adapt to heatwaves, but who gets to shape that adaptation, and whose needs are prioritised in the process.

Friends of the Earth believes that a fair response to the climate crisis must centre those most at risk — including older and disabled people, who are often overlooked in emergency planning. Our recent legal challenge to the UK Government’s National Adaptation Plan exposed its failure to protect frontline communities from increased threats, including heat. But what could the solutions look like? After yet more record-breaking temperatures, it’s a good time to share the learnings from this recent student design challenge.

Global perspectives

Because of the short timeframe for these projects, the speculative nature of the brief and few of the students having local connections, we explicitly invited them to draw on international examples and family experiences from around the world. And they did. Across the groups, students referenced personal conversations with relatives in China, Thailand and India and adapted ideas from places like Berlin, Shanghai, Bangkok and Dhaka to suit the UK context.

And despite the challenges, they also thought creatively about local insight. One group spoke to a disability inclusion consultant and reached out to local disability rights groups. Another bravely took their research questions into the local Wetherspoons.

Putting empathy at the heart of design

One of the most powerful threads running through all the student projects was the depth of empathy they developed through personal conversations. These interviews, especially when combined with the students’ own international perspectives, transformed abstract challenges into urgent human stories.

A student from China, for example, interviewed her grandmother about her community’s strategies for coping with heatwaves in Shanghai. What emerged was a story not just about physical adaptation, but about solidarity: neighbours checking in on each other, community-run spaces where elders could gather to cool down, and different cultural norms around mutual care.

Another team member shared that their grandfather in northern England didn’t see heatwaves as a health threat. He’d lived through many summers, he said — “what’s one more?” But the student noticed how exhausted and disoriented he became during the hotter days. That dissonance — between perceived and actual risk — became a touchstone for their design.

Several groups highlighted how older interviewees, especially those living alone, spoke less about the heat itself and more about the emotional toll of isolation. One student reflected:

“It wasn’t the temperature that scared people most. It was the thought of having no one to call if things went wrong.”

That led to creative yet grounded ideas like a daily phone care service, which connecting volunteers with isolated older people during heatwaves. Students designed simple tools — such as log sheets and safeguarding training for volunteers — to make this service both personal and safe.

“It’s not just about the heat”: key themes from the research

Across the groups, five key themes emerged:

- People underestimate how dangerous heat is. Despite recent experience of heatwaves in 2022, people do not see themselves at risk and do not make the connection between symptoms like dizziness, fatigue, or breathlessness and heat (particularly when the question is asked during the winter). This reflects Shade the UK’s analysis of the challenge. They were also unaware of the secondary risks of extreme heat, such as power outages.

- There’s an information – and a trust - gap. As well as not recognising the symptoms of heat distress, some interviewees weren’t aware of existing services or didn’t know how to access help during heatwaves. A lack of high-profile consistent messaging from local public services increases vulnerability (what would the equivalent of the Act FAST campaign for heat distress look like, for example?)

- Asking for help feels stigmatising. Older people interviewed for the project in the UK often said they didn’t want to be a burden and avoided reaching out even when they were struggling. (This was less the case in some other countries, such as China, where older interviewees expected to rely on community meal deliveries during heatwaves). This led to students trying to think about structures for mutual aid – and a focus on what people could offer each other.

- Isolation is the real emergency. For people living alone with limited mobility, in the context of an overstretched care system, heatwaves can quickly become frightening. One student shared that their interviewee already regularly drinks less water to avoid using the toilet — a hydration strategy that can be fatal in high temperatures. Resilience is relational. It’s not just what you know or what you have — it’s who will check in on you when the power goes out.

- Tech won’t fix this – but relationships might. Several groups explored ideas for apps or digital platforms in their early designs — but scrapped or adapted them after initial testing because of digital exclusion issues. At the same time this experience highlighted the fact that there is huge diversity within the target population, particularly with regard to tech literacy. Whilst this led groups to prioritise direct-contact and neighbourhood-level relationships, the opportunities for scale associated with tech-based solutions means they should not be quickly discounted.

What can we learn from elsewhere?

From China, students drew on the “Didi Card”. Didi card is primarily a transport card, that operates in cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen, but it also grants older adults access to subsidised transport, community services, medical care and even companionship programmes. Crucially, residents can also earn additional credits for things like leisure activities when they contribute (for example by providing care to a neighbour), rooting the model in reciprocity rather than dependency.

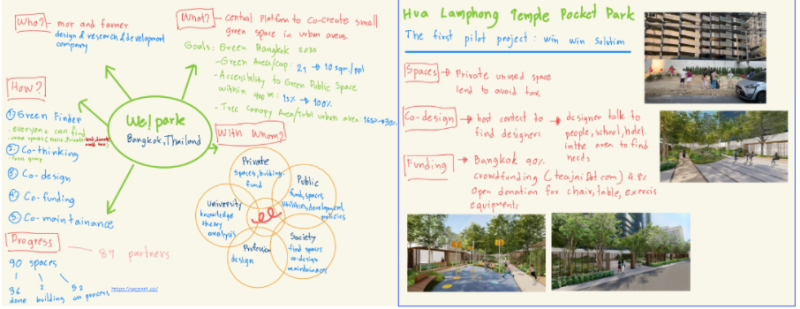

They also highlighted much higher levels of urban greening: tree canopy cover in Shenzhen is approaching 40%, compared to Bristol’s 17%. From Chengdu, they learned about how community spaces are adapted to become cooling centres (including community-kitchens with specially adapted menus). From Thailand, they examined We!Park — a data-led approach to empowering local people to identify and take ownership of space for urban greening (an idea that could build on our own Postcode Gardener model).

In Bangladesh, low-cost localised early warning systems are integrated with existing infrastructure, such as schools and mosques, to increase trust. Several European cities – including Paris and Athens – are now using the Extrema app, which evaluates the real-time personalised health risk of the user, provides alerts, recommendations and routing instructions to the nearest cooling centres. Although the focus was on building community capacity, they also explored technology solutions: could a SMART-watch like YourStride be easily adapted for bespoke heatwave alerts?

What were their solutions?

The students explored lots of solutions in the early stages, from free ice-cream vans to rooftop and community-led greening schemes.

Overall the most promising interventions included:

- Opening university spaces as cooling centres in the summer. These buildings were chosen because they are under-occupied when the need is greatest.

- A ‘kind bank’ system, where older and disabled users can request or offer help, products, or time-based services, integrating remote and in-person help. This could be both chatbot and telephone-based, focused initially on areas of the city most vulnerable to heat risk (through the combination of poverty and poor infrastructure). This system has wider implications than just heat resilience of course.

A key takeaway

Across the board, students expressed how their perceptions of climate adaptation had shifted. They began the project thinking about things like fans, insulation or green walls — and ended it talking about trust, dignity, shared responsibility and designing for people who don’t see themselves as vulnerable.

Designing for climate resilience isn’t just about infrastructure. It’s about relationships — between people, between generations, and between what we say we value and what we actually invest in.

What next?

We see this project as part of a wider conversation about placing community at the heart of adaptation strategies. We’d love to hear from any local authorities or voluntary sector organisations keen to learn more and interested in taking a design to the next level. Or piloting a project. The mutual aid idea is not new – so where is it already working well in the UK and how could this best be adapted for climate resilience?

These students reminded us that resilience isn’t just about staying cool — it’s about staying connected. We don’t need to wait for funding to get started on that.