Mary Stevens24 Mar 2022

A couple of years ago I facilitated a workshop about tree cover in Belfast. During a getting-to-know-you session, one of the participants explained that seeing The Man who Planted Trees on TV as a child was what set him on his journey towards environmentalism. Thirty years later he was still talking about it. Animations have extraordinary story-telling power and his experience is far from unique. Today’s young people often cite Wall-E or the Studio Ghibli films as key moments in their development, for example.

I was reminded of the Belfast story in the introduction to a workshop I attended on animation and the environment at the University of Bristol. As Dr Rayna Denison explained, animation is so effective for telling environmental stories for three reasons: first, its capacity for abstraction. Animations can give form to the invisible or the intangible. Think of the spirits in Frozen 2 for example, but also what animation could do to portray carbon dioxide or air pollution. Second, it lends itself particularly well to melodrama, as this capacity for abstraction and for exaggeration works strongly on our feelings. Finally, the tradition of anthropomorphism engages our empathy and allows the non-human world to tell its own story. How many young marine biologists have started a career because they loved Finding Nemo?

But these animations are huge, multi-million-dollar affairs requiring years of painstaking work. How can we as researchers or activists incorporate animation into our work? Fortunately, Sophie Marsh and Helena Haughton were there to guide us through the process. One of the joys of Bristol is that in one small room we had academics from the Cabot Institute for the Environment, including a lead IPCC author, a lead academic on Blue Planet II and animators who had worked for Aardman and Channel 4. The idea behind the workshop was that we would build on the conclusions of the recent IPCC report to create an animated response.

After a line-drawing warm-up exercise, Sophie and Helena introduced us to two basic techniques: the boil and the morph (how to make a bus turn into a cloud, for example, in five easy steps). From there we worked in groups to create simple storyboards telling the story of a change we had made in response to the climate emergency, or a solution we need. In my group we focused on the power of collective action to reduce anxiety and produce change: jagged angry thought bubbles above people’s heads (abstraction!) turned into a gentler cloud when they all came together, enabling the seeds of new ideas to germinate and flourish, ultimately creating a thriving eco-system for people and nature.

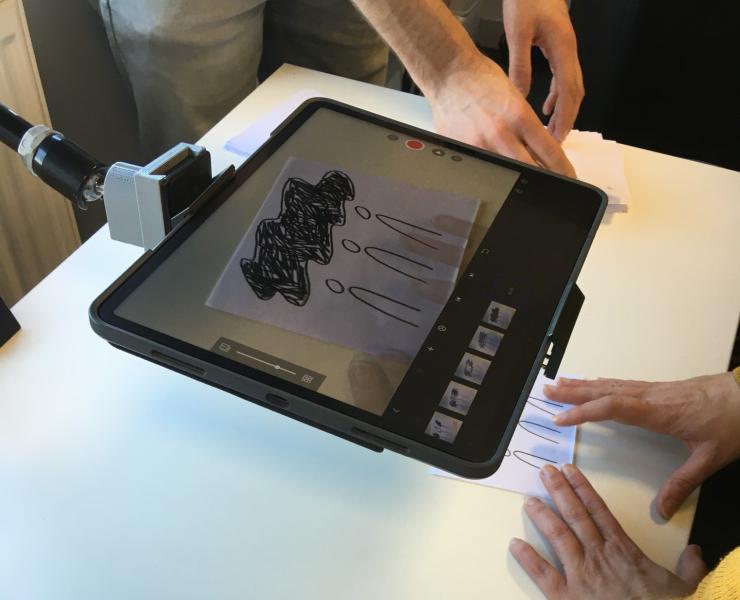

In not much more than an hour we produced 63 frames, and filmed them using Stop Motion studio (Da Vinci Resolve was also mentioned for editing – of course other software is also available). Sophie then edited all the films together and by the end of the afternoon we had produced about 20 seconds of stop-motion animation. The final version will be available soon, once Sophie’s smoothed out the rough edges (yes, I did manage to get my hand in shot at least once).

I came away with three main reflections:

- Animation is a really powerful tool for forcing groups of people to clarify their narrative. In order to make the storyboard we all had to agree on the beginning, end and intermediate steps. An animation workshop could be really useful as part of campaign development or any activity that requires people to develop a theory of change.

- The participatory and practical element is really powerful in creating a group dynamic and building trust. We were also able to have more relaxed conversations around the table, because we were also making and doing with our hands. It’s an important leveller too - most of us were not ‘artists’ but it didn’t matter.

- Animation – and illustration - can help us see things afresh. I thought I had largely digested last week’s IPCC report findings, but the Cabot Institute’s illustrations really drew my attention to the fact that the report is as much about solutions as it is about problems.

The Cabot Institute is already taking these tools out in the world, for example working with young people in Cornwall. You can also follow their work on Twitter. Meanwhile, this workshop has inspired me to think creatively about how we tell some of our more complex and abstract campaigning stories and bring to life the future we want to create. I’d love to see our My World My Home students trying out some of the techniques. I could imagine incorporating animation into our workshops or design sprints. And it also gave me the confidence and the language to think about how I could collaborate with animators in the future.

Special thanks to Dr Camilla Morelli for organising the event and inviting me to take part.