Christian Graham09 Jun 2022

As somebody who has often been charged with confronting colleagues with ideas of what radically different future could be on the horizon – and experiencing the looks of confusion, incredulity and sometimes outright cynicism that result – I am always looking for ways to bridge the understanding and especially, the action gap.

As Futures researcher, Bill Sharpe suggests, we can think of the future as moving towards us across three horizons:

- Horizon 1: Business as usual

This is the current state of affairs. - Horizon 2: Disruptive innovation

These are innovations which may be captured to further H1 or help forge a path towards H3. - Horizon 3: Emerging future

This is a vision of a better future we’d like to see.

Kate Raworth of Donut Economics has a great explainer about the “three qualities of the future visible in the present”.

She explains that this approach is not a predictor of the future but it can enable more nuanced conversations to take place and new insights to emerge.

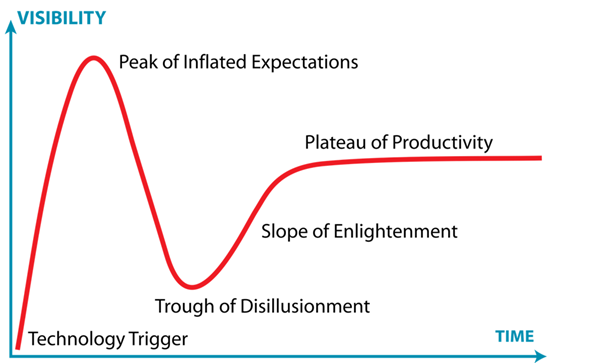

But watching this, it’s easy – especially when considering Gartner’s hype cycle - to see why organisations and business can be reluctant to invest any significant resource in a radically different but potentially mythical future - rather than simply extending out, and optimising, the present business as usual.

Gartner’s hype cycle proposes a journey that each new technology must undertake. The danger is we invest significant time and resources in the wrong thing or at the wrong time. This is particularly true if the thing we’ve invested in never emerges out of the trough of disillusionment. Examples of this abound, including most pre-bitcoin digital money alternatives such as Beenz.

In addition, we have a lot invested in business as usual – and some of us have spent entire careers optimising our organisations for it. Some may even have lobbied their governments to perpetuate it. This is often simply good management as organisations need some level of stability and security. Further, for every breakthrough technology or business model that results in a transformed future, sometimes dozens of alternatives lie abandoned or forgotten. “Whatever happened to x, eh? That never took off, did it?”, some will say with a knowing smile.

A recent chat with a colleague in IT reminded me just how difficult it is to operate outside of a prevailing business as usual paradigm. As far as IT is concerned, they suggested the current approach for most organisations is to simply lurch from one business as usual state to another. With IT in particular, it is simply too difficult and expensive to do anything else.

With one area of exception.

Business continuity and disaster recovery plans are an organisation’s attempt to manage risk and improve resilience in order to keep going during times of extreme stress through scenario planning.

Many will have seen their business continuity and disaster recovery plans severely tested during the pandemic as various previously unthinkable scenarios, such as everyone having to work from home, were played out.

Contained within many of these plans are a heady mixture of tried and tested approaches and technologies – and radical thinking. For example, key cloud service provider down? Try an open source alternative instead. Can’t get to the office or travel? Maybe video conferencing would work. Need to manage caring responsibilities alongside working? We’ve all managed with colleagues bouncing children and pets on their knees in zoom meetings and/or taking a quick time out.

Many of these seemed unthinkable even a few years ago, but many are now widely accepted as part of business as usual.

It's tempting to think such plans can only be conservative in nature – to rely on the tried and trusted, and even if not – there will be a snap back to the norm once the immediate crisis is over. But as we emerge from the coronavirus pandemic, contained within those sometimes hastily drawn up plans are a transformed vision of the workplace with less travel, more home working and increased flexibility of work patterns. The disaster forced the pace of change where different ways of doing things were practicable.

Maybe, in designing and testing our plans to keep the lights on in preparation for the radically unexpected, there are opportunities to explore a different world of the possible.